This is the second post in my series on analytics and aboriginal litigation

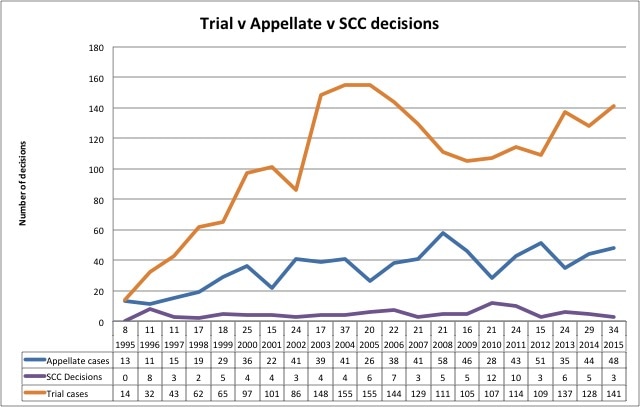

The focus of this post is on how analytics can reveal some interesting facts about the relative importance of different issues and different cases in aboriginal law. The big question is ‘what is the most important aboriginal law decision rendered between 1995 and 2015?’

Please note that I’m not asking which case had the most influence over aboriginal law during that period, just which aboriginal law decision was the most influential. The distinction, if you haven’t picked up on it yet, will become apparent.

Since I’m using a dataset by CANLII, I measure the ‘influence’ of a case in terms of how often it was cited by other cases in the CANLII dataset. Naturally, this is somewhat limiting, in the sense that ‘influence’ is reflected only in terms of those cases reported through CANLII (there are boatloads of unreported cases decided every year).

I expected that Haida would likely be the most influential, although since it was decided in 2004 and this dataset runs from 1995 to 2015, I would figure that perhaps VanderPeet or Delgamuukw, both seminal cases, might ultimately win out. Man, was I wrong (kinda).

The most cited aboriginal law case during that period, and by a wide margin, was British Columbia (Minister of Forests) v. Okanagan Indian Band. That right there should tell you a lot about how aboriginal rights litigation (and really a lot of other litigation) works in Canada.

To be fair, Okanagan isn’t really an aboriginal rights decision – it has far reaching implications, well beyond aboriginal rights law. The core holding of Okanagan relates to an advanced cost order.

The point of an interim costs order is to provide claimants counsel with funding as they advance litigation. This allows the case to proceed, and most important for claimants counsel, allows them to continue to be paid to advance the claim. This decision was, in essence, a finding that aboriginal rights lawyers could be entitled to an award of interim costs. This is no small matter in aboriginal rights law, as many of these cases can stretch over decades and can cost claimants (in this case a First Nation government) millions of dollars to prosecute. It’s a natural outgrowth of pursuing aboriginal rights claims through civil litigation (as anyone who has seen the film ‘A Civil Action’ would surmise, one popular strategy in civil litigation is for wealthy litigants to use procedural rules to drag out and increase the cost of litigation, making it more likely to both get a favorable settlement and to deter future litigation. Few litigants have deeper pockets than a government, which literally has a mint at its disposal. This can obviously present a problem for claimants counsel, who need a constant source of funding to advance a case, and in many cases lack a mint of their own.

Okanagan is the one aboriginal rights case which is extremely helpful to lawyers, and hence, is the most cited case in my inventory. And don’t pick on counsel for claimants exclusively. Consider that counsel for the Crown also have incentives for advanced cost orders: increased pace of litigation means more demand for Crown attorney, more overtime and most important in government, more prestige for Crown counsel working in aboriginal rights. In a very real sense, if you’re a lawyer working in aboriginal rights cases, Okanagan should be a total winner for you.

Even if you happen to be one of the few devoted aboriginal rights lawyers barely scraping by to advance your client’s rights, or a claimant, Okanagan is also great news for you because it enhances access to justice. Without this decision, its quite likely that many claims brought by impecunious clients might never see the light of day. Of course, to figure out how many, you’d need to examine the cases where Okanagan was cited (something I could do, but never got around to) to assess the efficacy of advance cost orders to enhance access to justice particularly for indigent clients. That’s some other project which would benefit from the application of this analytic.

Also, please consider that this is drawn off the same search logic I used in my initial post. That means it excludes cases like Gladue…quite likely a case which is cited much, much more often than any of these other cases. Sad, but true, I would suspect the number of reported (and more importantly unreported) cases which cite Gladue is likely several orders of magnitude greater than anything I would discuss in this blog.

To get to the numbers, at the time I ran this data, Okanagan was cited by 517 other cases, yet Delgamuukw, an older and foundational case in aboriginal rights law, was cited 455 times and at number three on my list is Lameman.

Of these three cases, Delgamuukw is the one which most people would consider a ‘win’ for the claimant. I certainly wouldn’t, mainly because the core result in Delgamuukw was to remand the case: the claimant neither ‘lost’ nor ‘won’ any remedy. Okanagan is a definite and clear ‘win’ for the lawyers working on behalf of indigenous peoples (and more important for the principle of access to justice), but isn’t a decision about the merits of the broader dispute in front of the court. Similarly, Lameman is a decision which holds that limitation periods apply to certain types of aboriginal rights claims. I imagine Lameman is so popular because the Crown likely invokes it quite frequently in order to dispose of claims, without the need to proceed to the merits of the case.

In other words, the three most cited cases between 1995 and 2015 (as of early 2016) were a foundational decision on aboriginal title, oral evidence and possibly consultation, a decision which ensures counsel gets compensated and a decision which establishes a powerful technical defense for the Crown. What’s most interesting to me, is that of the three ‘most important’ cases I identified, none of these cases actually resolved a dispute between indigenous peoples and the Crown: at least not on the merits of the dispute.

That right there sends a pretty powerful message about the state of aboriginal rights advocacy during that period of time. One can only hope that the period 2015-2025 will see something quite different, at least in terms of address the core disputes between aboriginal claimants and the Crown.

The focus of this post is on how analytics can reveal some interesting facts about the relative importance of different issues and different cases in aboriginal law. The big question is ‘what is the most important aboriginal law decision rendered between 1995 and 2015?’

Please note that I’m not asking which case had the most influence over aboriginal law during that period, just which aboriginal law decision was the most influential. The distinction, if you haven’t picked up on it yet, will become apparent.

Since I’m using a dataset by CANLII, I measure the ‘influence’ of a case in terms of how often it was cited by other cases in the CANLII dataset. Naturally, this is somewhat limiting, in the sense that ‘influence’ is reflected only in terms of those cases reported through CANLII (there are boatloads of unreported cases decided every year).

I expected that Haida would likely be the most influential, although since it was decided in 2004 and this dataset runs from 1995 to 2015, I would figure that perhaps VanderPeet or Delgamuukw, both seminal cases, might ultimately win out. Man, was I wrong (kinda).

The most cited aboriginal law case during that period, and by a wide margin, was British Columbia (Minister of Forests) v. Okanagan Indian Band. That right there should tell you a lot about how aboriginal rights litigation (and really a lot of other litigation) works in Canada.

To be fair, Okanagan isn’t really an aboriginal rights decision – it has far reaching implications, well beyond aboriginal rights law. The core holding of Okanagan relates to an advanced cost order.

The point of an interim costs order is to provide claimants counsel with funding as they advance litigation. This allows the case to proceed, and most important for claimants counsel, allows them to continue to be paid to advance the claim. This decision was, in essence, a finding that aboriginal rights lawyers could be entitled to an award of interim costs. This is no small matter in aboriginal rights law, as many of these cases can stretch over decades and can cost claimants (in this case a First Nation government) millions of dollars to prosecute. It’s a natural outgrowth of pursuing aboriginal rights claims through civil litigation (as anyone who has seen the film ‘A Civil Action’ would surmise, one popular strategy in civil litigation is for wealthy litigants to use procedural rules to drag out and increase the cost of litigation, making it more likely to both get a favorable settlement and to deter future litigation. Few litigants have deeper pockets than a government, which literally has a mint at its disposal. This can obviously present a problem for claimants counsel, who need a constant source of funding to advance a case, and in many cases lack a mint of their own.

Okanagan is the one aboriginal rights case which is extremely helpful to lawyers, and hence, is the most cited case in my inventory. And don’t pick on counsel for claimants exclusively. Consider that counsel for the Crown also have incentives for advanced cost orders: increased pace of litigation means more demand for Crown attorney, more overtime and most important in government, more prestige for Crown counsel working in aboriginal rights. In a very real sense, if you’re a lawyer working in aboriginal rights cases, Okanagan should be a total winner for you.

Even if you happen to be one of the few devoted aboriginal rights lawyers barely scraping by to advance your client’s rights, or a claimant, Okanagan is also great news for you because it enhances access to justice. Without this decision, its quite likely that many claims brought by impecunious clients might never see the light of day. Of course, to figure out how many, you’d need to examine the cases where Okanagan was cited (something I could do, but never got around to) to assess the efficacy of advance cost orders to enhance access to justice particularly for indigent clients. That’s some other project which would benefit from the application of this analytic.

Also, please consider that this is drawn off the same search logic I used in my initial post. That means it excludes cases like Gladue…quite likely a case which is cited much, much more often than any of these other cases. Sad, but true, I would suspect the number of reported (and more importantly unreported) cases which cite Gladue is likely several orders of magnitude greater than anything I would discuss in this blog.

To get to the numbers, at the time I ran this data, Okanagan was cited by 517 other cases, yet Delgamuukw, an older and foundational case in aboriginal rights law, was cited 455 times and at number three on my list is Lameman.

Of these three cases, Delgamuukw is the one which most people would consider a ‘win’ for the claimant. I certainly wouldn’t, mainly because the core result in Delgamuukw was to remand the case: the claimant neither ‘lost’ nor ‘won’ any remedy. Okanagan is a definite and clear ‘win’ for the lawyers working on behalf of indigenous peoples (and more important for the principle of access to justice), but isn’t a decision about the merits of the broader dispute in front of the court. Similarly, Lameman is a decision which holds that limitation periods apply to certain types of aboriginal rights claims. I imagine Lameman is so popular because the Crown likely invokes it quite frequently in order to dispose of claims, without the need to proceed to the merits of the case.

In other words, the three most cited cases between 1995 and 2015 (as of early 2016) were a foundational decision on aboriginal title, oral evidence and possibly consultation, a decision which ensures counsel gets compensated and a decision which establishes a powerful technical defense for the Crown. What’s most interesting to me, is that of the three ‘most important’ cases I identified, none of these cases actually resolved a dispute between indigenous peoples and the Crown: at least not on the merits of the dispute.

That right there sends a pretty powerful message about the state of aboriginal rights advocacy during that period of time. One can only hope that the period 2015-2025 will see something quite different, at least in terms of address the core disputes between aboriginal claimants and the Crown.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed